On Wednesday, April 8, 2020, Dr. Paul Takhistov from the Department of Food Science at Rutgers led a discussion regarding food safety, food availability, and biosecurity in light of COVID-19—an issue that MBS students had identified as a major concern and/or interest via a survey in the March 2020 MBS Community Connectivity Initiative.

“Good evening everybody,” Takhistov began. “[Just] one more day in the COVID-19 pandemic.” Relatively speaking, April 8 was a quiet news day as far as COVID-19’s impact on the U.S. food industry.

Over the next 72 hours, reports on major news media outlets emerged, describing a situation that just did not make sense. They showed images of consumers looking at empty grocery store shelves and miles-long lines at food banks while farmers, left with an abundance of crops, were forced to destroy them because they had no buyers or means to transport their goods. Interviews with consumers—grocery store clerks and shoppers scrambling to purchase essentials—were juxtaposed with those of farmers who were forced to destroy their crops and dump millions of gallons of milk, which further illustrated this imbalance.

Then, on April 12, 2020, Smithfield Foods exploded into the news when it shuttered its South Dakota pork processing plant amid a severe coronavirus outbreak. The plant—one of the largest pork processing facilities in the U.S. –was quickly identified as a COVID-19 hotspot, with nearly 700 confirmed cases as of April 19, 2020. The shutdown “remove[d] an important link in the supply chain that connects farmers and consumers,” impacting up to five percent of the nation’s pork supply.

Dr. Takhistov’s lecture provided an overview of the U.S. food supply chain. His talk underscored the complexities of the U.S. food supply and identified its weak spots. It helped in understanding the potential impact that the Smithfield Foods incident, or other similar incidents, could have on the public’s ability to access food.

America’s Food Network

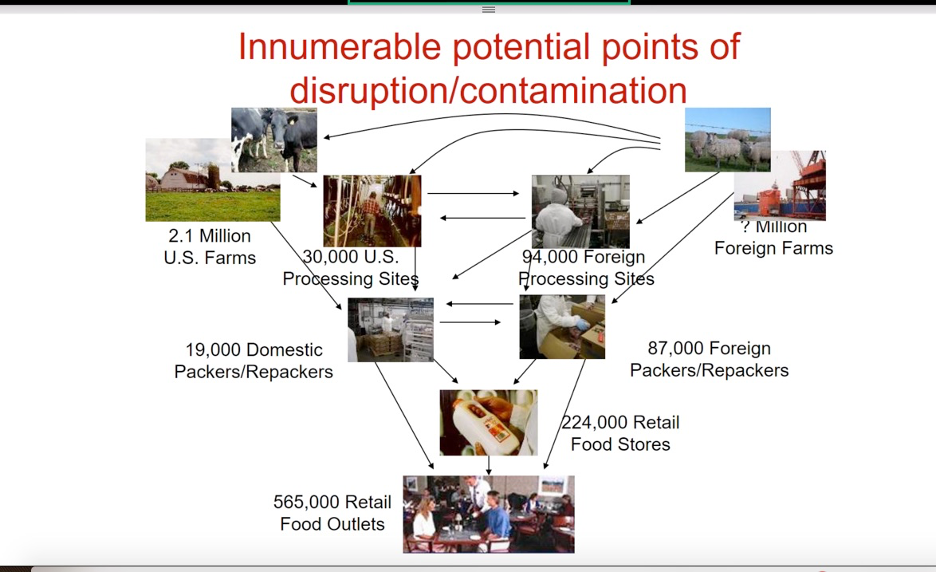

“The food supply chain may be the most complicated supply chain in the world,” said Takhistov, noting that for the United States—the world’s largest importer and exporter of food—the “chain” is actually a vast, complicated network of growers, suppliers, and distribution channels that are highly dispersed geographically, with no centralized system and innumerable opportunities for disruption and contamination (as depicted in the below image).

Additionally, the network is not overseen or governed by just one agency, but rather eight or nine federal entities including the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Food & Drug Administration (FDA), the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency), and the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). “It is largely self-regulated,” says Takhistov.

Food Availability

The United States imports a staggering number of food products; however, the U.S. is also “relatively insulated” (per the USDA) against food shortages. Most essential foods are sourced and available within the U.S.—particularly, important protein sources such as beef, pork, and poultry. Further, there is no evidence that COVID-19 can be transmitted through food or its packaging, according to the USDA and CDC. So there is no risk that COVID-19 will directly infect food sources.

“We can't rely on other countries during a pandemic, though,” says Takhistov, noting that some nations have shut borders entirely. So, what will be impacted?

Produce: Roughly 68 percent of all vegetables and 45 percent of all fruits consumed are grown outside of the U.S.

Mexico supplies roughly half of all imported vegetables and about 40 percent of all imported fruit. Items include avocados, tomatoes, cucumbers, blackberries, and raspberries. The U.S. also imports heavily from Costa Rica, which supplies everyday staples like bananas and coffee.

Bottom Line: Experts agree that there won’t necessarily be a food shortage; rather, Americans may not have the foods they want to eat when they want them. For example: Jersey corn and tomatoes will remain (hopefully bountiful and) available during the summer months, but you can probably say goodbye to popping succulent red grapes from Chile during the winter. People will need to adapt to what food is available.

COVID-19: Non-Foodborne, and Lethal to the Food Industry

According to Takhistov, one out of every six jobs in the U.S. is related to food. COVID-19 is not foodborne, but it is potentially lethal to the most valuable (and vulnerable) link in the nation’s food “chain:” the workers who help move food products from fields and factories to consumers. These include the laborers who harvest produce and cut meat, the truck drivers who haul food items across the country, and the warehouse workers, cashiers, stockers, and store clerks who ensure the public’s access to food in their communities. Many of these workers are now falling seriously ill or dying—risking their lives while serving as a vital (and often unrecognized) link that holds the food supply chain together.

An Abundance of Food, A Shortage of Workers

As the national unemployment rate soars, the food industry is experiencing a serious labor shortage—one that’s only going to become worse, says Takhistov.

The closing of the Smithfield Foods pork plant highlights the importance of food-industry workers and also their vulnerability. It shows how a lack of consideration for worker safety can have wide-ranging effects. It also underscores dynamic that has existed for years: jobs in the food industry are plentiful; many American workers just don’t want them. So, this pandemic emphasizes more than ever that protecting human resources is critical to maintaining food security in this country.

The 2016 Agricultural Workers Survey found that 69 percent of all documented agricultural workers were from Mexico. Only 24 percent were born in the U.S. Similarly, the majority of workers at Smithfield Foods’ South Dakota plant are immigrants who are paid low wages to do labor-intensive, unappealing work.

To combat this labor shortage, companies in the food industry are offering incentives, bonuses, and pay increases to attract and retain workers—some are even asking office staff to help with production.

According to Takhistov, as of April 8, 2020:

- J.M. Smucker Co. was paying workers a $1,500 bonus

- JBS SA, is giving a $600 bonus to unionized workers

- Conagra Brands is giving a $500 bonus.

- Cargill, Campbell Soup and National Beef are giving hourly workers a $2 bump.

- General Mills was asking office staffers to volunteer at plants as it tries to keep up with production levels.

Food Provision: The Grocery Store

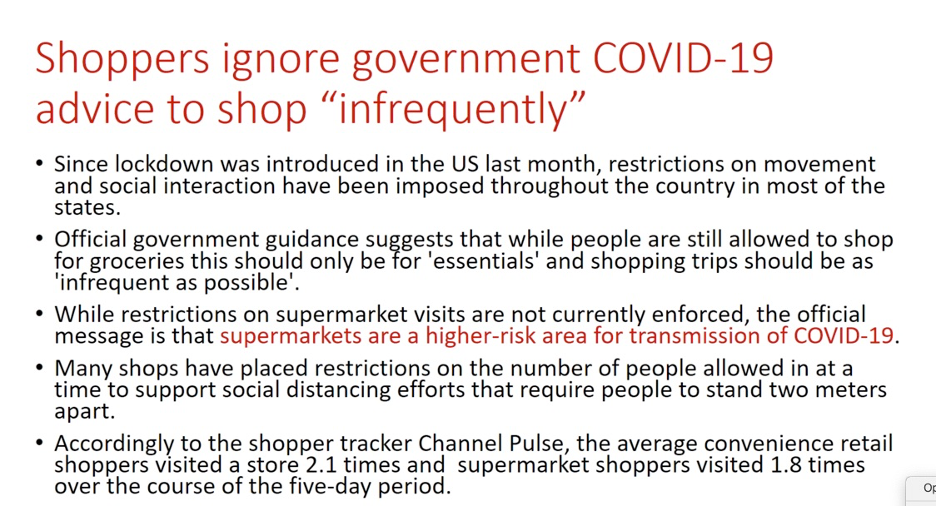

Trips to the grocery store are essential—we all need to eat. Unfortunately, the supermarket is a high-risk site for COVID-19 exposure and/or transmission, simply due to the congregation of people. In-person trips are now mostly the only option. The days of getting Instacart groceries in under an hour—or securing any delivery or pickup slot at all—are over. As one consumer dourly noted, nailing down an online shopping time slot “is like winning the world’s most pathetic lottery.”

Directives recommend infrequent shopping; however, that poses a challenge when your store is constantly out of staples like milk, eggs, and cleaning supplies. More stringent rules and restrictions have been implemented to increase workers’ safety and further limit virus transmission:

Sign of the Times: The Return of Plastic Bags

Plastic bags—once considered a scourge on our planet and scheduled for phaseouts in many cities and states—have now been determined as the safest and most sanitary way to transport groceries out of the store. Those fancy reusable bags we were all encouraged to buy? You can put them away for now.

See our sidebar for additional shopping safety.

To Conclude

Just as consumers are at the literal end of the food chain, we are concluding this post with a slide regarding food preparation: the end-step of the journey for your food product, which likely arrived safely in your shopping cart after a complicated journey—one that was only possible because of the work of others.