Innovative Thinking + a “Can-Do” Attitude = a Revolutionary Lab Experience in the Age of COVID-19

By Jen Reiseman-Briscoe and Beth Ann Murphy, Ph.D.

On March 17, 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic rapidly spread through the northeastern U.S., Rutgers University officials announced that all classes and in-person events would be suspended into the month of May. With no clear guidance on the status of summer courses, Beth Ann Murphy, MBS’s then-new Life Sciences Coordinator, began evaluating which classes would be impacted or potentially cancelled. Kristina Kannheiser’s broad-based lab course, Personal Care Applied Science Laboratory, immediately came to mind.

“This particular class is offered only in the summer semester,” says Murphy. “For certain students, if this class was part of a graduation plan, then not being able to take the course would impact their timeline.” The more she thought about it, Murphy, a 25-year veteran of Merck & Co. and an alumna of Rutgers School of Graduate Studies Ph.D. Program in Biomedical Sciences, saw no reason why course instruction and lab work could not be conducted remotely.

“Readying a remote/online lab is not a novel concept, but setting up a virtual lab course would be something entirely new for MBS,” says Murphy. “Since personal care science (PCS) is a rapidly growing part of the MBS program, my feeling was ‘if we really want to expand our offerings and accommodate student demand, then this course would be a critical addition to our online curricula.’” A growing number of PCS students live well outside the New York / New Jersey geographical area, says Murphy, and applications for the program are steadily increasing. “More so than I expected,” she adds.

Murphy had no doubt that the lab would be a success. All she needed, she said, was a willing partner. And maybe not even that. “Because when people tell me that something can't be done, I’m like, ‘well, you're wrong.’”

Kannheiser was immediately on board. “The world is changing—it is becoming more digital, and we need to embrace that,” she says. “The best way to do that is by thinking outside the box and using creative thinking to make things work.”

The Experiment Gets Under Way

As soon as the class was offered as an online course, it immediately filled to capacity. Mei-Ly Chua, a lead research scientist in charge of color cosmetics and hygiene products for a New Jersey-based manufacturer, called the offering “a once-in-a-lifetime” opportunity. “As an online student,” she says, “I typically wouldn’t be able to take an in-person lab class. But with COVID-19 shifting everything to remote learning, I could.”

Chua says that she was aware of the MBS program—particularly the PCS concentration—long before enrolling as a student and was excited about this particular course because of its broad industry value. “It was the perfect class to allow me to expand my existing knowledge base of personal-care formulations.”

Students were able to conduct high-quality experiments from afar...and were still graded on 15-to-20 page lab reports to justify their methods. Pictured: analysis of powder behavior in different cosmetic oils.

While outfitting a proper laboratory in a home environment is doable, there was a ton of work and hustle involved in shifting a lab course online quickly. “There was a lot of planning obviously in the beginning—a lot of logistics,” says Kannheiser, who, along with Murphy, had to strategize and coordinate how students would receive all necessary equipment and raw materials in time for class…during a pandemic.

All raw materials were shipped directly to students; Kannheiser and Murphy also generated an Amazon-friendly list for necessary glassware and instruments.

Additionally, as MBS’s first-ever remote lab class, Kannheiser and Murphy also had to design the course curriculum from scratch due to the many new elements and issues—some pandemic-related, some not—that needed to be addressed. First and foremost was ensuring that the students’ remote/virtual lab experience simulated the one they would have experienced in the non-virtual world. To that end, there were numerous legal and safety issues to consider—all of which presented significant concerns.

“We made sure that there was a safety module in the course, which is what would happen in a non-virtual lab, anyway,” said Murphy. Basically, “we forced students to acknowledge a list of rules: ‘Even though you're in your home, make sure you wear shoes while you're doing experiments. Don’t let your kids play with things. Don’t eat things.” The latter two directives, as silly as they sound, were particularly important points to acknowledge. “A lot of my students are adults with children,” says Kannheiser. With schools closed and most daycare options eliminated due to COVID-19, if students had young kids, those kids would likely be home. While “do not taste lab reagents” is a standard mandate covered in nearly all lab safety modules, says Kannheiser, “this was something we needed to emphasize.”

Kannheiser ultimately arranged for all raw materials to be sent to her house; she then assembled and shipped individual kits to students via FedEx. As far as providing equipment, Murphy and Kannheiser decided that shipping pipettes, spatulas, scales, and other glassware and measuring tools might be too ambitious given tight timelines and shipping delays caused by COVID-19. They instead generated and sent to students an item-by-item, Amazon.com-friendly materials list and then crossed their fingers that all equipment would arrive on time.

Mei-Ly Chua (L) and Kathryn Panichella (R) creating products and evaluating color matches.

Of course, there was also skepticism about whether experiments performed remotely could be of the same caliber as those performed in physical labs. “That’s what I said to Beth from day one,” said Kannheiser. “People were thinking ‘cooking in the kitchen,’” she says, adding, “I was pretty sure that that would be the biggest hurdle we’d face.” Kannheiser and Murphy stayed the course; both knew that if the lab went well, it would open the door to conducting virtual labs for other MBS courses, and, importantly, would also make it possible for this particular lab to be held more than once a year. Overall, it would make MBS’s courses more accessible and widely available to students living in regions outside of the New York/New Jersey/Philadelphia metropolitan areas. Kannheiser, personally, sees such remote labwork as inevitable.

“Ten years ago, you got an online degree and it didn't really count for anything. But now, it's real. Esteemed universities, Rutgers included, are offering fully online degree—and this is the way of the future. Companies like Google and Twitter have announced they aren't going to require employees to return to the office, potentially ever,” says Kannheiser. “So, actually, this is the future.”

The Experiment Begins

Everyone anticipated technical glitches and equipment delays, but the biggest challenge turned out not to be anything related to labwork, but something universal to all virtual / remote learning: communication. For many students, being part of a virtual work group was a brand-new experience. Then, there was Kannheiser’s intentional focus on sharpening students’ written communication skills via four 15-to-20-page lab reports on which students were primarily graded. “Conveying ideas clearly and concisely is critical to success in the personal care industry,” she says.

Virtual Teamwork – Getting Settled

First, there was the business of settling into assigned groups. Kathryn Panichella, a food science major who is well-established in her career in the food and beverage industry, says that communication was key from the get-go. “Especially to work out schedules and evaluate how long projects would take, since we have to group-effort the whole thing.”

Time-management was a challenge that students had to tackle, as well. “You’re not in a physical classroom anymore, with a lab held every week from 6:30 p.m. to 9:30 p.m.,” says Panichella. Instead, “Professor Kannheiser gave us free rein to conduct four labs over three months. So we all had to look at calendars and figure how to accomplish the experiments in ways and timeframes that worked for all of our schedules,” she says. “Of course, I have a job that I do 9 to 5.” Meanwhile, as companies abruptly shifted to “work from home” culture, many working students lost the structure of a true workday and were suddenly juggling school, job responsibilities, and home lives with very little structure at all.

“Getting on the same page, just picking out [specific] days or hours that, ‘OK, [we are] going to work on this experiment at this time,’ was critical,” said Panichella—especially, she said, since some experiments took four hours to complete, while others took up to two weeks. While the lab’s primary course objective is to increase scientific knowledge while honing chemistry skills, “communication is something that people should really focus on when doing this course,” says Panichella, “especially if students are taking the lab online.”

For Chua, a flexible schedule was a bonus. “I appreciated that we were able to work at our own pace,” she says. “As a working professional, this was very helpful when I had other priorities with tight deadlines that needed to be met.” Chua said that each member of her team was accommodating and collaborative, and, together, they were able to make each other's schedules work.

“We were all in the same time zone, too, so that made things easier,” she says. What surprised her most, she says, “was to see that students in the MBS program are from all over the U.S.—and the glob[e]! In my other class, I had a teammate from Singapore.”

Virtual Teamwork: Getting to Work

With each of the four labs (surfactants, emulsions, powders, and anhydrous), said Panichella, “Professor Kannheiser was like, ‘I'm going to put you in a laboratory setting. You're going to get a customer who has all of these requests. Using the materials you have, can you come up with a formulation?” Kannheiser then added an extra challenge, says Panichella. “She made the experiments tricky—and I actually applaud her for doing this: not everybody in the group received the same materials—on purpose. And it forced our group to collaborate with each other instead of doing individual assignments.”

Chua and Panichella, both of whom work in state-of-the-art laboratories and are well-established in their careers, described the initial frustration of trying to communicate with lab mates virtually as opposed to in person. “It was a completely new experience,” said Chua, who was deemed an essential employee (she formulates hand sanitizer and disinfectants) and continued to commute to work as usual throughout “stay-at-home” restrictions. “Even when I was an undergraduate, we did not rely so heavily on technology like we do today—with screen-shares and phone calls. In a lab together,” she says. “It is so much easier to be able to write out equations and explain things to my colleagues in person, using visuals.” Panichella agreed. “In my lab at work,” she says, “I'm constantly collaborating with others. But communication is completely different online.”

Finally, no group project would be complete without the dynamic that emerges in almost all projects involving teamwork, regardless of class format: “Group work can become a challenge when different members have different perspectives on how things should be done,” says Chua. “In the end, though, we pulled together to accomplish a common goal.”

Kannheiser was pleased with the students’ online collaborations. “For students to build a solid working relationship with each other—that’s something I really strive for in my class. In the real world,” she says, “you don’t get to choose your colleagues, and learning how to work with different personalities—especially when working virtually—is a huge benefit.”

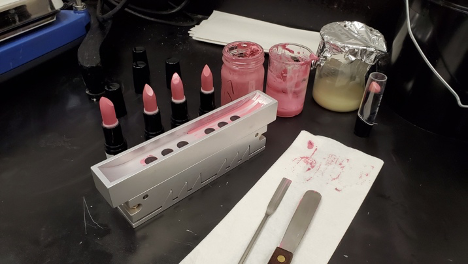

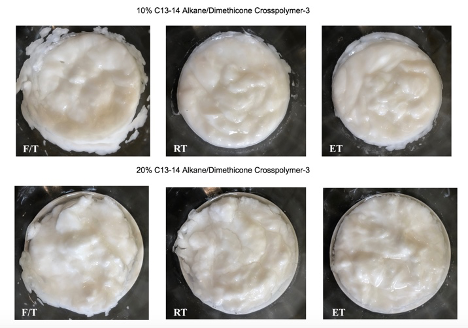

Formulating emulsions and testing their stability.

In-Person vs. Remote Labwork: Measuring Knowledge, Comparing Quality

So, how was learning measured? “Just as in the in-person lab class, students were required to submit lab reports, and they're graded on those reports,” says Kannheiser. “Cosmetic chemistry is its own unique animal,” she explains. “If you're an analytical chemist or an organic chemist, there are a lot of highly standardized methods. With personal care, it's very much taking things from all different scientific disciplines and trying to make it work for what you need to prove.”

For this reason, Kannheiser heavily weighs how the students explain and defend their methods and how well they articulate their rationale in each lab exercise. “I always tell students that there isn't a wrong answer,” says Kannheiser, “but they need to prove scientifically why they chose what they did. It's scientific reasoning that I'm grading—I'm more concerned with their thought process.” Kannheiser gives students initial guidance, “but then I leave a lot up to students’ interpretation(s), because they’re graduate students, they're chemists, and I want them to use their brain.”

Mei-Ly Chua, an essential employee during COVID-19, often stayed late at work to complete assignments, but she also conducted several experiments from home, including the experiment pictured above: surfactant foam height analysis. “I never imagined I’d be able to test surfactant stability and foam heights in pajamas with TV going on in the background—but I did.”

Kannheiser stresses that the main goal of her course is to ensure that students have the basic lab skills necessary to excel in a PCS industry setting. “In the real world,” she says, “students are not going to get step-by-step instructions. They're going to get, ‘I need you to prove to me that this raw material is better than another one’ and that’s it. No further direction. And they're going to have to figure it out.”

Clear, succinct writing is another element that is critical to success in the personal care industry, says Kannheiser. “Writing memos, reports, and emails is a daily part of my job,” says Panichella. “Half of the time, I'm on the bench developing a drink, but the other half of the time, I'm sitting at my desk typing up formulas and finishing costings for our customers and sending and answering messages.”

Kannheiser, herself, says that early in her career, she experienced a steep learning curve to master how to communicate like an industry professional. Simply restating observations, she says, “does not fly. Often, you are not given a detailed protocol or instructions beyond ‘prove to me that this raw material is better than that one.’ The personal care scientist has to be able to figure this out on his or her own, and then explain it—all with little or no direction.”

Epilogue

By all accounts, the course was a success; it accomplished everything it set out to do and more. “I was pleased with the outcome and am happy that we were able to meet our students’ needs and overcome the obstacles that COVID-19 put in our way,” says Murphy. When the course began, say Murphy and Kannheiser, there was a lot of uncertainty—with everything. “At the end,” says Kannheiser, everyone was very confident. “Everyone worked with their groups really well. And everyone really embraced virtual learning,” says Kannheiser.

The quality of students’ work was excellent as well, says Kannheiser, noting that reports were more comprehensive than those she’s received in previous years. “I think that students were taking more time to think through the lab,” she says. Most importantly, “students learned how to ‘prove to me that this raw material is better than that one’—with little or no guidance.”

So, did students really work in their pajamas? Chua, an essential employee, says she mainly conducted experiments at her workplace out of convenience; it was easier to stay after hours at her laboratory and conduct experiments from there.

However, she did carry out some experiments at home. “I never thought that I would be able to test surfactant stability/foam heights while sitting at home in my pajamas with the TV going on in the background,” she says, “but that’s exactly what I did.”

As for ‘cooking in the kitchen,’ “This isn't like a cute little fourth grade science experiment,” says Panichella. “We are actually developing and making things that a customer could ask for. We are learning the backbone about what raw ingredients are used and how can we approach making products using the materials we have on hand.”

Revathi Nair, who already has one master’s degree in perfumery technology, concurs with the excellence and quality of the virtual lab work. “Professor Kannheiser did an exceptional job pulling things together for us to carry out those experiments at home,” she says. “All the required raw materials were shipped to us, and we only had to get equipment like glassware, weighing balances, etc., to conduct the trials. While the laboratory environment was missed, the quality of the experiments was maintained—it was excellent.”

“It was an ideal time to try something like this,” said Murphy. “We had an excuse [with COVID-19]. It might have gone badly. “ But it went great. “I had totally made up my mind that lab won’t be possible this summer due to the pandemic,” says Nair. “But kudos to Professor Kannheiser and Dr. Murphy for making this happen.”